Later this month, our organisation, The New Zealand Initiative, will take a large delegation of top New Zealand business leaders to the Netherlands. It is not a trade mission but an ideas exploration. We want to see what makes the Dutch tick and what makes the Netherlands successful.

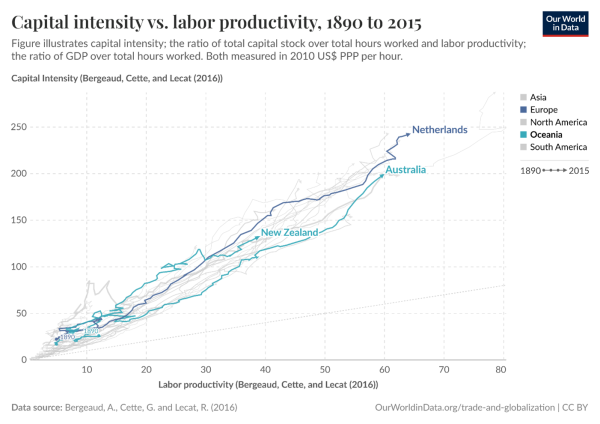

As I was preparing materials for our delegation, one graph caught my attention. It tracked capital intensity and labour productivity for both countries from 1890.

For seven decades, the lines moved in parallel. Sometimes New Zealand edged ahead, sometimes the Netherlands. Nothing remarkable there.

Then came the 1960s. The Dutch line began climbing steeply. By the mid-2010s, the Netherlands registered nearly twice New Zealand’s levels on both measures. That means their workers produce twice as much per hour worked with twice the capital supporting them.

This single graph captures New Zealand’s economic underperformance better than most lengthy policy reports.

(Source: Our World in Data, https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/capital-intensity-vs-labor-productivity?time=earliest..2015&country=AUS~NLD~NZL)

What happened? The standard explanation is familiar. Britain’s eventual entry into the European Economic Community in 1973 ended New Zealand’s preferential market access – and Australia’s, too, of course. It was an economic shock for both countries, and it took a long time to absorb.

This explanation contains a grain of truth. But it is insufficient.

The economic divergence between the Netherlands and New Zealand began well before Britain joined the EEC. As a founding member in 1957, the Netherlands was already positioning itself at the heart of European integration. The 1960s saw the Common Market take shape, creating opportunities the Dutch seized with both hands.

When Britain finally joined in 1973, the blow to New Zealand was severe. But by then, the Netherlands had spent over a decade building its advantage. European integration meant access to a rapidly growing market. Rotterdam could serve the entire continent. Foreign investment would bring capital and know-how.

The Dutch saw the opportunity and grasped it with both hands. Meanwhile, New Zealand saw disruption and retreated.

The difference shows most clearly in New Zealand’s treatment of foreign investment. The country maintains some of the OECD’s most restrictive rules for overseas investors. The Overseas Investment Act scrutinises, delays and often deters foreign capital.

Wellington treats international investment as something dangerous that requires careful management by bureaucrats.

Consider how this looks from abroad. A multinational company surveys the Asia-Pacific region. Australia may not be particularly welcoming to foreign capital either, but with 27 million people, companies need to be there. Singapore and many other Southeast Asian nations actively court investment.

And New Zealand? Forms to fill, permissions to seek. For most global firms, New Zealand remains at best a “nice to have” – a small, distant market that was never essential to begin with, now made even less attractive by regulatory hurdles.

The chain of consequences is predictable. Less foreign investment means less capital per worker, which holds down productivity, wages and living standards.

New Zealand compounds the problem through further policy choices. Banking regulations, however well-intentioned, push banks toward the perceived safety of residential lending. Startups and small businesses struggle to access capital while mortgage lending booms.

Despite the market liberalisation of the 1980s and 1990s, Wellington’s officials retained a planning mentality. Too many still believe markets need their guidance, that foreign investment requires their approval, that they know better than entrepreneurs what the economy needs.

This mindset created a regulatory system that protects incumbents while deterring new entrants. Compliance costs are high. The Resource Management Act has become legendary for delay and expense. Professional licensing requirements multiply. Each rule may seem defensible in isolation. Together, they form a barrier to competition.

The result is predictable. Many New Zealand sectors end up dominated by a handful of players. This is not their fault – it is just the logical conclusion of an overregulated and overprotected economy.

New Zealand is not poor. But the country has chosen to allocate capital poorly – and then plan and regulate whatever happens in the economy.

The result of all this is that Dutch workers today operate with far more capital at their disposal – modern machinery, world-class facilities, sophisticated systems – and that capital is also more productively employed.

Meanwhile, New Zealand workers have less capital per person than many developed economies. They compensate by working harder – about 300 hours more per year than their Dutch counterparts. The country works hard but not smart. Economists call this poor total factor productivity.

Over time, this highly regulatory and capital-scarce environment has shaped how New Zealanders approach business itself. The “number 8 wire” mentality – that Kiwi pride in making do with whatever is at hand – works against systematic investment in advanced technologies and processes. The tall poppy syndrome discourages ambitious success.

But culture does not emerge in a vacuum. Policy and culture reinforce each other in a cycle of modest ambitions and mediocre outcomes. These patterns may seem fixed, but none of this was inevitable.

At each decision point, alternatives existed. New Zealand could have welcomed foreign investment as a source of capital and expertise. It could have designed regulations that encouraged competition rather than protecting incumbents.

Still, past choices need not determine future outcomes.

I look forward to learning more when we visit the Netherlands later this month. It is one thing to read about capital intensity. It will be quite different seeing it in the Port of Rotterdam, the world-class food cluster of Wageningen, or the sophisticated wastewater heat-to-energy plant in Utrecht.

I hope we will return with an understanding of what becomes possible when a small nation decides to be open rather than defensive, ambitious rather than comfortable, connected rather than isolated.

The Dutch made their choice. New Zealand and Australia can still make theirs.

To read the full article on The Australian website, click here.