The Reserve Bank of New Zealand has one big job when it comes to monetary policy.

That job is defined in its Remit – the contract that it has with the government.

It must keep future annual inflation between one and three percent over the medium term, targeting the midpoint of that range.

It is currently being beaten up for doing that job.

Last week, former Prime Minister Sir John Key told Mike Hosking that the Bank should have cut interest rates far more aggressively. Prime Minister Luxon, last month, also said he believed the Bank should have cut interest rates more aggressively.

The criticism of the Bank stepped up with a much weaker quarterly GDP announcement than had been expected.

But the criticisms really miss the mark.

It is not that the Bank is faultless – the Bank erred substantially in 2020 and 2021, partially through poor forecasting, and partially through a poor underlying understanding of the economic shocks it was facing.

It is rather that the Bank is currently doing the job set out in its Remit. Inflation is back within the bounds set by its Remit. Inflation expectations are also back within bounds – a vast improvement on early 2023’s blowout in both inflation and inflation expectations.

Worse, the criticism is coming from a government that is not making the Reserve Bank’s job easier, while the Governorship of the Bank is still in play – apparently decided, but not yet announced.

My last column discussed the problem in context of Reserve Bank independence.

This week, the New Zealand Initiative released a short Note defending the Bank against recent critiques.

Suppose that the critics were right and that the Bank had been far too aggressive in tightening monetary policy after the excesses of 2020 and 2021. What would the economy look like, right now?

We would not just see high unemployment and low growth. We would also see inflation outcomes below the Bank’s target, and inflation expectations over coming years undershooting that target.

The annual Inflation rate dropped to 2.2% in September 2024 and has risen slowly since then to 2.7%. It is still within the target range set by the Bank’s Remit, but it is certainly not below the midpoint.

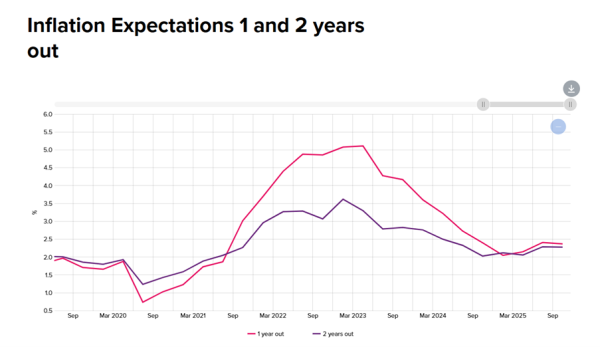

The Bank’s latest Monetary Policy Statement also shows that inflation expectations are within-bounds. In 2022, survey respondents expected inflation to be well above the top of the Bank’s target range even two years ahead. By December 2024, those expectations again looked anchored to the Bank’s target band.

If the Bank really had tightened ‘too aggressively’, inflation outcomes would be undershooting the target, or expected future inflation would be.

Instead, inflation hovers in the upper ranges of the target band and inflation expectations are around where they should be.

Those expectations matter. When the Bank’s inflation target is credible, high current inflation does not mean high expectations of inflation in two years’ time because everyone expects the Bank to do what is necessary to meet its inflation target. Those expectations make it easier for the Bank to meet its target because people do not start banking on continued price increases.

In 2022 and 2023, inflation expectations were not anchored in the Bank’s target range.

The Bank did not just have to fight inflation. It also had to re-establish credibility that it had lost during the Covid period.

Unfortunately, fiscal policy made the job harder.

Budget 2024 maintained high levels of fiscal stimulus – despite being popularly characterised as austere. The government reduced taxes while maintaining high levels of spending, covering the gap between the two with borrowing – while promising reduced spending in future.

Deficit spending in a recession can be defensible. The government’s tax take declines in a recession, and spending on social support programmes increases. But this is not the story of the 2024 or 2025 deficit. Those deficits are structural – the kinds of deficits that do not go away even if the economy reverts to its normal performance.

The IMF considered New Zealand’s 2024 cyclically-adjusted primary deficit – that is to say, the deficit after we strip away the effects of the economic cycle – as being among the largest in advanced economies.

Fiscal policy was stimulatory at the same time as monetary policy was trying to get inflation back in line. Monetary policy always accounts for what the government is doing on the fiscal side. Had the government avoided running fiscal stimulus, the Bank could have cut interest rates more quickly.

So where does that leave us?

The Reserve Bank shifted back to doing its One Big Job once it became clear that inflation had gotten away from it.

The government could have made the Bank’s job easier by getting the fiscal side back in order. Had it done so, monetary policy could have taken a more accommodative path – interest rates could likely have come down more quickly.

Instead, the government maintained substantial structural deficits while second-guessing the Bank’s interest rate decisions.

Here’s hoping for better fiscal choices in May 2026, and for less blaming of the Bank for doing its job.

The Initiative’s note Monetary Policy without Mates, coauthored by Dr Eric Crampton, Dr Oliver Hartwich, and Dr Bryce Wilkinson, is available here.

To read the full article on the Newsroom website, click here.