On 5 December 1933, ninety years ago this week, America ended alcohol prohibition.

Fourteen years of prohibition had reduced drinking, but at a terrible cost. Organised crime took over what had been a legal and taxed market. Gang warfare over alcohol became common. And adulterated black market alcohol caused a lot of harm.

Had Americans of 1933 been able to send a message back in time, they would have warned their predecessors not to go ahead with prohibition in the first place. Prohibition is terrible policy for harm reduction. The best time to end prohibition is before starting it.

In 2022, Labour legislated that tobacco prohibition would take effect from 1 April 2025.

Alcohol prohibition in America had exempted ‘near-beers’ containing trivial amounts of alcohol. Tobacco prohibition in New Zealand was to exempt cigarettes containing trivial amounts of nicotine. But the harm from smoking is in the byproducts of combustion, not the nicotine.

Two weeks ago, the incoming National-led government announced its coalition agreements.

The coalition agreements promised to undo the legislation. Prohibition would end before it even started, so New Zealand would not need to learn the lessons of prohibition the hard way.

And a whole lot of people quickly seemed to lose their minds.

New Zealand’s tobacco prohibitionists have argued that the Coalition’s abandoning prohibition will cause immense harms to health. They claim worries about illicit markets are simply industry-backed fearmongering.

Looking back to the debates from 2022 might help restore some minor amount of sanity.

They argued that the Ministry of Health’s modelling was “significantly flawed” and that the assumptions in that modelling were “massively overestimating the likely impact of that policy.”

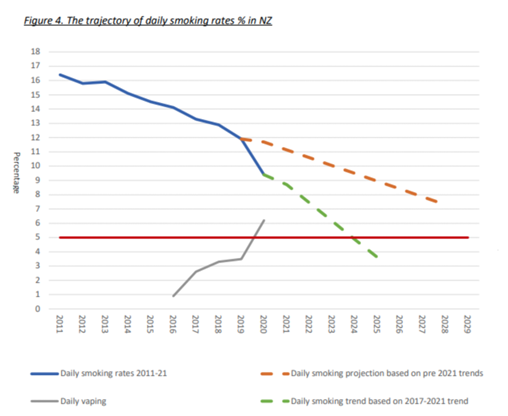

ASH’s submission also suggested that New Zealand was on track to hit the SmokeFree target without the package of legislation. Rapid shifts into vaping meant a sharper decline in smoking rates that needed to be considered.

Source: ASH. Submission to the Health Select Committee. August 2022.

Because the Ministry of Health had underestimated ongoing declines in smoking rates, and overestimated the decline in smoking that might be caused by tobacco prohibition, the health benefits of the package of policies were overstated.

The health costs of not going ahead with prohibition are consequently a lot lower than are currently being claimed.

ASH also warned that the Ministry of Health had not accounted for shifts to illicit sales or other ways of circumventing prohibition. Their submission noted that the illicit market is relatively small currently, but that the policy change would require “significant mitigations” to deal with the illicit market.

Tobacco excise of $1,678 per kilogram has already encouraged an illicit trade that makes up between 6 and 11 percent of the local market – again, figures as cited in ASH’s submission.

We can also look across to Australia, where The Guardian reports that firebombings are now part of turf wars over illicit tobacco. Officials in Victoria suspect that a “large proportion of the tobacco industry has been infiltrated by serious and organised crime.”

Under prohibition, the illicit market would not just be a way of avoiding excise. It would be the only way of getting a real cigarette. It would be remarkable if Australian crime syndicates, or others, did not plan on supplying the New Zealand market from 2025 – had we gone ahead with prohibition.

Tobacco prohibition would not have prohibited nicotine; vaping would remain legal. But illicit tobacco does not carry excise. Shifts to the illicit market provide no health benefits while reducing excise revenue. And because illicit tobacco is cheaper than taxed tobacco, smokers who shift to the illicit market would have one fewer reason to flip to vaping.

National’s coalition agreement with New Zealand First also promises to reform the regulation of other reduced-harm alternatives: oral tobacco and smokeless nicotine products.

Chewing tobacco has long been banned in New Zealand. But the legislation currently also bans snus, an oral tobacco pouch that is less risky than chewed tobacco and far less risky than smoked tobacco. Snus has been an important part of Sweden’s decline in smoking rates. Legalising it here would provide one more alternative for those wishing to quit smoking and who have not found vaping appealing.

Look past the often-partisan rhetoric. The coalition’s promise to avoid tobacco prohibition will hardly convert the country to smoking. It will instead mean that New Zealand continues its path toward lower smoking rates as more smokers shift to a broader range of reduced harm alternatives.

Had America dodged alcohol prohibition, America’s temperance campaigners would have been very angry.

But the very best time to end prohibition is before beginning it. New Zealand has dodged a bullet.

To read the article on The Post website, click here.